| • Day Tours from Palermo: Regularly-scheduled with frequent departures: Erice-Segesta, Agrigento, Monreale, Piazza Armerina. | • Shore Excursions from Palermo: Private shore trips in western Sicily: Monreale, Palermo, Erice, Segesta, Cefalù. Cooking classes too. | • Tours around Sicily with departures almost every week of the year. See the whole island! |

| • Sicily Concierge: Personalized travel in Sicily. Unusual itineraries and unique travel experiences. Exactly what you're looking for. | ||

BUYER BEWARE: These services are offered by a real travel agent – the kind with experience, an office (with land-lines) and full-time employees. Not just a guy with a smart phone and tablet running a business out of his car – much as we love our cars, smart phones and tablets. A growing number of independent "guides" found on the internet offer excursions (driving you from place to place). Unfortunately, most of them are not licensed as tour guides, tour operators or taxi drivers. This means that they probably lack accident insurance that covers a client who (for example) incurs an injury while walking around an archeological site, such as the temples at Agrigento and Segesta. Worse yet, some of these "guides" may deceive you into believing that they are licensed when they are not. In Italian law, only a properly licensed company qualifies for the insurance described. In a similar trend, some taxi drivers deceptively promote themselves as tour operators. In Italy the tourism/travel industry is highly regulated for your protection. (Read more about us.)

Welcome to the world's most conquered city!

A multicultural legacy in one timeless place where North

meets South and East meets West

![]() t's in the air.

t's in the air.  And in the splendid

churches, castles and palaces. A touch of the Classical with a taste of the Medieval and the Baroque. Even the food is a polyglot cacophony of flavours from every era: Phoenician, Greek, Carthaginian,

Roman, Gothic, Byzantine, Arab, Norman, Swabian, Angevin, Aragonese. Palermo has been home to Phoenician traders, Roman patricians,

Arab emirs, Norman kings and at least two medieval Holy Roman Emperors, and the spirit of each lives on.

And in the splendid

churches, castles and palaces. A touch of the Classical with a taste of the Medieval and the Baroque. Even the food is a polyglot cacophony of flavours from every era: Phoenician, Greek, Carthaginian,

Roman, Gothic, Byzantine, Arab, Norman, Swabian, Angevin, Aragonese. Palermo has been home to Phoenician traders, Roman patricians,

Arab emirs, Norman kings and at least two medieval Holy Roman Emperors, and the spirit of each lives on.

A Style of Diversity

What is Palermo? This eclectic crossroads of Mediterranean and

northern European civilization is more than a museum. It's a vibrant — even chaotic — city whose unique culture has been forged and molded by three

millennia of history emerging from three continents. There's no other place on earth like Palermo, and to discover the history of this

singular city is to experience something of the diverse worlds that have created something which has evolved into its own culture.

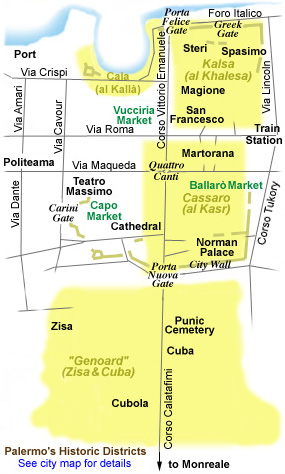

The streets of old Palermo are an intriguing labyrinth of outdoor markets, subtle niches and long-forgotten secrets — almost a subculture unto themselves. After nine centuries street markets still evoke the atmosphere of Arab souks. Only the Baroque churches and palazzi on the same narrow streets remind you that you're in Italy, but then "Italy" has existed as a modern concept only since the middle of the nineteenth century; Sicily — ruled from Palermo as a Fatimid emirate and then as a Norman kingdom — transcends this by many centuries.

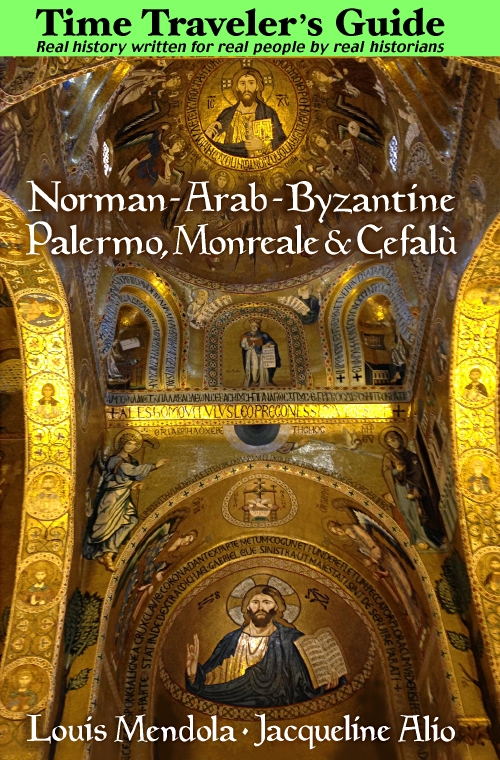

Palermo's Norman Palace epitomizes the city's heritage of diversity. It was built by the Normans upon the foundations of an Arab castle, al-Kasr. This, in turn, had been constructed in the ninth century on the site of a Punic (Phoenician-Carthaginian) structure. The Normans' first chapel, built in the Romanesque style very late in the eleventh century, is now the "crypt" beneath the Palatine Chapel of the twelfth century. Today all can be visited.

Beyond the "Golden Shell"

Of course, no royal capital ever survived on its own, separated from the rural environs that nourished it, and some of the places around Palermo

are not to be overlooked: Segesta and its ancient Greek temple, hilltop Erice with its Punic walls and medieval fortress, seaside Cefalù and

its medieval cathedral, Caccamo with its baronial castle on a mountain, and much more. Monreale Abbey is right next door, and the Phoenician-Greek-Roman colony of

Solunto is just twenty minutes outside town.

Palermitans call it the "Conca d'Oro," as though it were a golden seashell of orange groves and lemon orchards in the plains encircling this sprawling metropolis and lazily extending to the base of the rocky mountains that give the city so much of its rugged character.

Beyond this, there's a subtle world of streams, small lakes and rolling hills against the backdrop of steep peaks. There's the Ficuzza Woods to the south, the Madonie Mountains to the east and Sicily's Wine Country to the west toward Marsala.

Peopling of an Island

Peopling of an Island

The earliest

inhabitants of Sicily came to be known as the Sikanians, and from them the island inherited its most ancient

name, Sikania. Then came the Sicels and Elymians; it was the latter who founded the city which came to be

called Egesta and then Segesta. The Phoenicians founded Palermo, which they seem to have called called

Zis, as a trading post, joining Motya and Soluntum. Palermo was much contested during the Greek and Roman

wars against Carthage. The Greeks and Romans called it Panormos, meaning "all port," but under the

Byzantine Greeks Panormus was less important than Syracuse, the principal Sicilian city on the remote frontier

of Constantinople's influence. It was under the Arabs that, as Bal'harm, the city grew and prospered as never before, becoming one of the

Muslim world's most splendid cities, surpassed in its opulence only by Baghdad. During this period Sicily's population probably

doubled, with numerous towns being founded, particularly in the interior.

The Golden Age

The Normans' arrival in 1071 ushered in a "golden age" which lasted until the death of Frederick II in 1250. New castles were built as feudalism was introduced, along with

"western" Christianity (Catholicism), but the Norman and Swabian kings generally respected the religious rights of all Siclians: Normans, Byzantines, Arabs, Jews. By 1282, at the time of the Vespers uprising,

this remarkable age of tolerance was little more than a fond memory. Most of Palermo's Byzantine (Orthodox) Christians, and most Muslims, were by now Roman Catholic, and the Jews who did not leave had converted by 1495.

With the introduction of Aragonese rule Sicily found itself firmly rooted in the West, and Spanish rule followed. Sicily, of course, remained a kingdom, though just one of many dominions of the kings of Spain. Palermo became a seat of the Inquisition. If the Renaissance made few inroads here, the Baroque certainly did, and indeed art historians refer to an architectural style called "Sicilian Baroque."

A Taste of Sicily

Whatever you do in Palermo, even if you're here for only a day, don't overlook

the local cuisine. Sicilian food bears the mark of medieval influences. The Arabs introduced sugar cane, rice and certain citrus fruits, and the

strong flavors of caponata (aubergine and caper salad), arancine (filled rice balls), cassata and cannoli (both filled with a sweet ricotta cream) are tasty testaments to

the kind of culinary culture which evolves only over the course of centuries. Artichokes, harvested in winter and spring, are thought to be native to Sicily, while lamb and swordfish are so popular

that they might almost be considered "national" dishes.

© 2008-2017 Best of Sicily Travel Guide. Used by permission.